Copernicus av Jeremi Wasiutynski

Copernicus

Skaperen av en ny himmel

The Creator of a New Heaven

Av Jeremi Wasiutynski,

Gunnar Arneson (Oversetter)

Pris:

445,–

Innbundet

Utgivelsesår: 2017

I 1937 utga Jeremi Wasiutynski, polsk-norsk forfatter og astrofysiker, en biografi over Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) på polsk. Copernicus var den som skapte den første heliosentriske modell for planetsystemet siden antikken. I hele sitt voksne liv var Copernicus engasjert i det ermlandske fyrstebispedømme. Hans utdannelse i Krakow og Italia var finansiert og krevd av bispedømmet for å oppnå en stilling som kannik. Dette var et embete som krevde utdannelse i jus, kirkelig og sivil, samt medisin og matematikk som han fikk i Krakow, Bologna og Padova. Sin doktorgrad tok han i krikejus i Ferrara i 1503 som ligger omtrent midt mellom Bologna og Padova av grunner som stod hans personlighet nært. Doktorpromosjonen her var mindre prangende og mer i samsvar med hovedpersonens innstilling til sine fag. Hans onkel på morssiden var den myndige biskopen som ga både Nicolaus og hans bror Andreas slike embeter og muligheter. Broren Andreas fikk en vanskeligere skjebne med pengevansker og verst av alt en sykdom som var uhelbredelig og sosialt stigmatiserende. Sykdommen var lepra eller spedalskhet som faktisk var en sjelden sykdom i Polen rundt år 1500.

I 1937 utga Jeremi Wasiutynski, polsk-norsk forfatter og astrofysiker, en biografi over Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) på polsk. Copernicus var den som skapte den første heliosentriske modell for planetsystemet siden antikken. I hele sitt voksne liv var Copernicus engasjert i det ermlandske fyrstebispedømme. Hans utdannelse i Krakow og Italia var finansiert og krevd av bispedømmet for å oppnå en stilling som kannik. Dette var et embete som krevde utdannelse i jus, kirkelig og sivil, samt medisin og matematikk som han fikk i Krakow, Bologna og Padova. Sin doktorgrad tok han i krikejus i Ferrara i 1503 som ligger omtrent midt mellom Bologna og Padova av grunner som stod hans personlighet nært. Doktorpromosjonen her var mindre prangende og mer i samsvar med hovedpersonens innstilling til sine fag. Hans onkel på morssiden var den myndige biskopen som ga både Nicolaus og hans bror Andreas slike embeter og muligheter. Broren Andreas fikk en vanskeligere skjebne med pengevansker og verst av alt en sykdom som var uhelbredelig og sosialt stigmatiserende. Sykdommen var lepra eller spedalskhet som faktisk var en sjelden sykdom i Polen rundt år 1500.

In 1937, Jeremi Wasiutynski, Polish-Norwegian writer and astrophysicist, published a biography of Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543)in Polish. He was the one who created the first heliocentric model for the planetary system since antiquity. Throughout his adult life, Copernicus was engaged in the Archdiocese of Ermland. His education in Krakow and Italy was financed and demanded by the diocese to achieve a position of canon. This was an office that required education in law, ecclesiastical and civil, as well as medicine and mathematics in Krakow, Bologna and Padua. He received his doctorate in Church Law in Ferrara in 1503, located about the middle of Bologna and Padua for reasons close to his personality. The doctor’s promotion here was less ostentatious and more consistent with the prot subject’s attitude toward his subjects. His maternal uncle was the authoritative bishop who gave both Nicolaus and his brother Andreas such offices and possibilities. His brother Andreas had a more difficult fate with money problems and worst of all a disease that was incurable and socially stigmatizing. The disease was lepra , which was actually a rare disease in Poland around 1500.

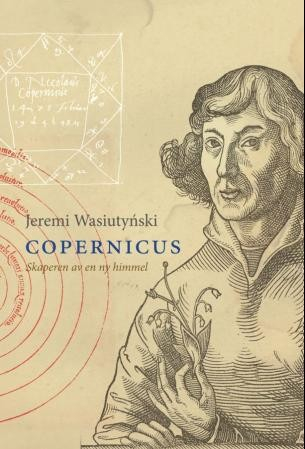

Nicolaus Copernicus, om faktisk aldri kalte seg akkurat ved det navnet, var født i Thorn (Torún på polsk) i dagens Polen 19. februar 1473 og døde 70 år gammel, 24.mai 1543 i Frauenburg (Frambork). Copernicus liv som voksen ble derfor preget av den lutherske reformasjonen som fikk en del framgang hos de tysktalende i Prøyssen som Ermland ble administrert under, mens astronomen og legen Nikolai Koppernigk forble trofast mot sitt katolske overhode selv om det ikke manglet på konflikter med den katolske øvrighet. Det er forøvrig interessant at det er lite som tyder på at den geistlige Copernicus var spesielt interessert i teologi eller teologiske stridigheter. Hans verden var målbare størrelser og himmelens geometri. Liljekonvallen som han lot seg avbilde med i levende live er et symbol for naturforskere, som den gangen ofte var knyttet til legeyrket og astrologien. Det vi i dag kaller astronomi ble ofte kalt teoretisk astrologi og derfor var det helt naturlig for ham å bli avbildet med konvallen og ingenting annet som på bildet på boka forside. Siden ble han avbildet med en modell av det heliosentriske system i hånden, men det uttrykte ikke naturforskerens eget bilde av seg selv og sitt arbeid. Som Newton la han grunnlaget for sitt arbeide gjennom å studere sine forgjengere både i middelalderen og antikken. Han beundret de antikke astronomene og brukte deres observasjoner som han anså å ha høy nok kvalitet til å kunne brukes også mer enn 1500 år seinere. Han lagde selv sine instrumenter og påstod aldri at han hadde noen større nøyaktighet av sine målinger av stjerner og planeter på himmelen enn antikkens mestre. På den tiden var man fullstendig klar over blant astronomene at observasjonene av månen og planetene ikke stemte dersom man regnet med de antikke regnemåtene for himmellegemenes posisjoner. Striden stod om tolkningen og dermed den grunnleggende kosmologiske modellen som kunne brukes til å forklare posisjoner i fortid og fram for alt i framtid.

Nicolaus Copernicus, if never really called himself by that name, was born in Thorn or Torun in Polish on 19 February 1473 and died at the age of 70 in Frauenburg (Frambork). Copernicus’s life as an adult was therefore characterized by the Lutheran Reformation, which gained some success from the German-speaking people in Prussia under which Ermland was administered, while astronomer and physician Nikolai Koppernigk remained faithful to his Catholic head, although there was no lack of conflict with Catholic authorities. Interestingly, there is little evidence that Copernicus was particularly interested in theology or theological disputes. His world was measurable sizes and the geometry of heaven. The lily-of-the-valley with whom he was depicted alive, is a symbol of naturalists, who were often associated with the medical profession and astrology. What we today call astronomy was often called theoretical astrology, and therefore it was only natural for him to be depicted with lily-of-the-valley and nothing else in the picture on the front page. He was then depicted with a model of the heliocentric system in his hand, but it did not express the naturalist’s own image of himself and his work. Like Newton, he laid the foundation for his work by studying his predecessors in both the Middle Ages and antiquity. He admired the ancient astronomers and used their observations that he considered to have high enough quality to be used more than 1,500 years later. He himself made his instruments and never claimed that he had any greater accuracy of his measurements of stars and planets in the sky than the Ancient Masters. At the time, astronomers were fully aware that the observations of the moon and planets did not match if the ancient calculations of the celestial bodies were expected. The controversy was about the interpretation and thus the basic cosmological model that could be used to explain positions in the past and forward for everything in the future.

Dette er en situasjon i tråd med den man hadde på 1800 tallet da Merkurs og Uranus bevegelser heller ikke fulgte daværende teori for planetbevegelsene. Merkurs konstante avvik på 43 buesekunder pr 100 år ble forklart i 1916 med Einsteins forbedrete modell av bevegelsene i hans generelle relativitetsteori og Uranus avvik fra teorien ble forklart og bekreftet med funnet av den nye planeten Neptun i 1846. En slik kontinuitet må vi også forholde oss til når det gjelder Copernicus’ arbeid rundt år 1500-1520. På samme vis som Copernicus lot stjernehimmelen og sola «stå stille» i stedet for Jorda lot Einstein tyngdekraften være et tilsynelatende og varierende fenomen i det tredimensjonale bildet erstattet med symmetrisk eller invariant fenomen i et firedimensjonalt bilde. Det fins etter hans teori ingen egen type akselerasjon som kan knyttes til tyngdekraften siden den ikke har egenskaper som kan skilles fra enhver akselerasjon. Den eneste forskjellen er at alle himmellegemer har null akselerasjon i det firedimensjonale bildet og dermed er «tyngdekraften» fratatt ansvaret for himmelens og jordens bevegelser. Dette var Einsteins variant av Copernicus forenkling ved å la sola og stjernehimmelen være ubevegelig i stedet for Jorda selv. Ved lesing av denne biografien over Copernicus er det mitt inntrykk at Wasiutynski ønsker å gjøre det klart hvilken kontinuitet det er fra antikkens verdensbilde til vårt moderne. Ikke et dramatisk brudd som man ofte får inntrykk av. Stadig er jo denne vitenskapshistorien fylt med arbeidet til naturforskere som må stå imot den alminnelige konsensus hos kollegaer og samfunnets bevilgende makthavere for å komme videre. Stadig må jo naturvitenskapen bevege seg mot en sannhet som ingen egentlig kjenner naturen til. Copernicus (del)prosjekt i så måte som endte opp i hans bok Revolutionibus var alltid hva Einstein kalte «Gelegenheitsarbeid», leilighetsarbeid, som han tok svært seriøst. Han var antakelig i koma nær sin død da hans venner lot ham ha ett eksemplar av boka i hendene våren 1543. Selv hadde han ingen etterkommere siden han levde et liv i sølibat. En ung husholderske som stelte huset hans på eldre dager ble brukt som argument for et mulig syndig liv, men ble aldri annet enn materiale for hans motstanderes svertekampanjer. Et arbeid fra 1517 som omhandlet penger og verdiforringelse av mynter foregrep økonomiske teorier som også ble anvendt etter hva jeg kan se da euroen ble innført i mange land i Europa i 1999. Kalenderreform som til slutt endte med pave Gregors reform i 1572 var en viktig motivasjon for Copernicus når han arbeidet for å forstå himmelegemenes bevegelse. Han skrev forslag om dette allerede 1515.

En betraktning han gjorde som lege er også verdt å nevne: en medisin virket ikke bedre om innholdslista var lang. I dag kaller vi det jo virkestoff som gjerne er en veldokumentert kjemisk forbindelse. På internett kan vi kjøpe «medisiner» med slike lange innholdslister. Kanskje selgerne av disse burde lese om Copernicus de også?

This is a situation in line with the 19th century, when Mercury and Uranus’ movements did not follow the theory of planetary motion. Mercury’s constant anomalies of 43 arcseconds per 100 years were explained in 1916 with Einstein’s improved model of movements in his general theory of relativity and Uranus deviations from the theory were explained and confirmed with the discovery of the new planet Neptune in 1846. Such continuity must also be dealt with in Coper’snicus work around the year 1500–1520. In the same way Copernicus, the starry heavens and the sun reliwiciated quietly in the scene of the Earth, Einstein allowed the gravity to be a seemingly and varied phenomenon in the three-dimensional image replaced with symmetrical or invarian phenomena in a four-dimensional image. According to his theory, there is no type of acceleration that can be linked to gravity, since it does not have properties that can be distinguished from any acceleration. The only difference is that all celestial bodies have zero acceleration in the four-dimensional image, thereby relating the impliedness of all celestial bodies for the movements of heaven and earth. This was Einstein’s variant of Copernicu simplification by allowing the sun and the sky to be motionless instead of Earth itself. By reading this biography of Copernicus, it is my impression that Wasiutynski wants to make clear the continuity of the ancient world view of our modern. Not a dramatic break that is often perceived. After all, this history of science is filled with the work of naturalists who must resist the general consensus of colleagues and the community’s granting powers to move on. Of course, science must continue to move toward a truth that no one really knows nature. Copernicus (part) projects that ended up in his book Revolutionibus were always what Einstein called the Young People’s Appealer’s Emergency Trials Work, which he took very seriously. He was probably in a coma near his death when his friends left him with a copy of the book in the hands of 1543. He himself had no descendants since he lived a life of celibacy. A young housekeeper who cared for his house in older days was used as an argument for a possible sinful life, but was never more than material for the smear campaigns of his opponents. A 1517 work dealing with money and the detrimentation of coins presumed economic theories that were also applied to what I can see when the euro was introduced in many countries of Europe in 1999. The calendar reform that eventually ended with Pope Gregory’s reform in 1572 was an important motivation for Copernicus as he worked to understand the movement of the heavens. He wrote suggestions on this as early as 1515.

A consideration he made as a doctor is also worth mentioning: A medication did not seem better if the inventory was long. Today, we call it a well – documented chemical compound. On the Internet, we can type up medicines with such long lists of contents. Maybe the vendors of these should read about Copernicus, too.

I sitt embete som kannik inngikk mye administrativt arbeid som han hadde dekket opp i sin utdannelse i Italia der kirkelig og sivil jus inngikk. Han tok utdannelse i matematikk i Bologna, verdens eldste universitet og medisin i Padova som på denne tid og langt senere også var et senter for denne vitenskapen der også engelskmannen Harvey, han som oppdaget blodomløpet, utdannet seg. Sin doktorgrad og endelige eksamen i kirkejus tok han i Ferrara der eksamen og festlighetene rundt dette hadde mer beskjedne former i kostnader og festprakt. Han startet sine studier i Krakow der han også hadde mange venner siden i livet. Etter 12 år som student fra 1491 til 1503 tok han opp sine embetsplikter i fyrstebispedønnet til sin onkel Lukas Watzenrode. En ikke helt ukontroversiell geistlig som visste å bruke sin makt i alle hans funksjoner. Han brukte heldigvis også sin makt til å gi sin nevø og tidens fremste astronom et livslangt embete som gjorde det mulig for naturforskningen å ta et svært viktig skritt mot det moderne verdensbildet.

In his office as a canon, there was much administrative work that he had covered in his education in Italy where ecclesiastical and civil law was included. He was educated in mathematics in Bologna, the world’s oldest university and medicine in Padua, who at the time and later was also a center of this science in which englishman Harvey, who discovered the blodd circulation, was educated. His doctorate and final exams in church law he took in Ferrara where the exams and festivities around it had more modest forms in costs and festivities. He started his studies in Krakow, where he also had many friends in his later life. After 12 years as a student from 1491 to 1503, he took up his duties in the princely body of his uncle Lukas Watzenrode. A not entirely uncontroversial clergyman who knew how to use his power in all his functions. Happily, he also used his power to give his nephew and the foremost astronomer a lifelong office that enabled science to take a very important step toward the modern world view.

Denne berørende okkultasjonen av Aldebaran 9.mars 1497 som Copernicus så fra Italia var avgjørende for hans oppgjør med antikkens teorier om månens bevegelse (Skjermbilde fra Stellarium)

Denne berørende okkultasjonen av Aldebaran 9.mars 1497 som Copernicus så fra Italia var avgjørende for hans oppgjør med antikkens teorier om månens bevegelse (Skjermbilde fra Stellarium)

This grazing occultation of Aldebaran 9th March 1497, Copernicus saw from Italy, was crucial to his reckoning with ancient theories about the motion of the Moon (image from Stellarium)

Boka inneholder det meste av det vi vet om den store astronomen i dag. Boka har et stort persongalleri og forteller om både de vitenskapelige og de mange praktiske gjøremål som hovedpersonen deltok i. Han var selv ikke særlig opptatt av sin person, men kunne overfor forskere han mente ikke holdt mål kunne han være nokså besk mot. En av hans samtidige ville ha det til at de antikke observatører ikke var til å stole på siden de i hovedsak ikke ga slike resultater som angjeldende forsker mente var den riktige modellen for bevegelsene på himmelen. Coprenicus brukte antikkens observasjoner som sine egne og brukte avvikene til å forbedre og ikke forringe deres modeller. Det er en viktig forskjell. Han kunne da sammenlikne med sine egne og vise avviket og påvise behovet for en forbedret modell ved å komme med mer nøyaktige posisjoner for himmellegemene.

Selv synes jeg Copernicus’ arbeid under ett er i samme ånd som Newtons prinsipp for naturfilosofien fra Principia fra 1717:(1)

The book contains most of what we know about the great astronomer today. The book has a large personal gallery and tells of both the scientific and the many practical activities in which the main character participated. He himself was not interested in his person, but could with scholars he felt that he could not measure up to him. One of his contemporaries wanted the ancient observers not to be trusted because they did not produce such results as researchers believed to be the right model for the movements in the sky. Coprenicus used ancient observations as his own and used the discrepancies to improve and not degrade their models. There’s an important difference. He could compare with his own and display the deviation and demonstrate the need for an improved model by making more accurate positions for the celestial bodies.

I myself think Copernicus’ work under one is in the same spirit as Newton’s principle of the the philosophy of the 1717 edition of Principia:

(1)«In experimental philosophy we are to look upon propositions inferred by general induction from phenomena as accurately or very nearly true, notwithstanding any contrary hypotheses that may be imagined, till such time as other phenomena occur, by which they may either be made more accurate, or liable to exceptions. This rule we must follow, that the argument of induction may not be evaded by hypotheses.

(I min ubeskjedne oversettelse: I eksperimentell filosofi må vi undersøke forslag som avledes generelt fra fenomener så nøyaktig eller svært nær sanne som mulig, uansett hvilke eventuelle motsatte hypoteser som kan tenkes, inntil andre fenomener inntreffer, hvorved de enten kan gjøres mer nøyaktige, eller antatt å være unntakelser. Denne regelen må vi følge, at argumentet om utledning fra fenomener ikke må erstattes av spekulasjoner.)

Å lese boka krever noe kunnskap om astronomi, og for den historisk interesserte gir den mye stoff om denne viktige brytningstid rundt reformasjonen og renessansen og alt hva den innebar av religiøst og politisk konfliktstoff. Dessuten, ikke minst det naturvitenskaplige nybrottsarbeid som den privat tilbaketrukne kannik i Ermland «Mikojan Copernigk» stod for i hele sitt voksne liv.

Boka er oversatt fra polsk med et godt og klart språk av Gunnar Arneson.

Reading the book requires some knowledge of astronomy, and for the historically interested it gives much material about this important refraction of the Reformation and the Renaissance and all of what it involved in religious and political conflict. Furthermore, not least the scientific revival work that the privately retbricant canon in Ermland was instrumental in Cardishcotta Copernigk stood for throughout his adult life.

The book is translated from Polish to Norwegian with a clear language by Gunnar Arneson.

Digital translation by SpeechNote

Legg igjen en kommentar